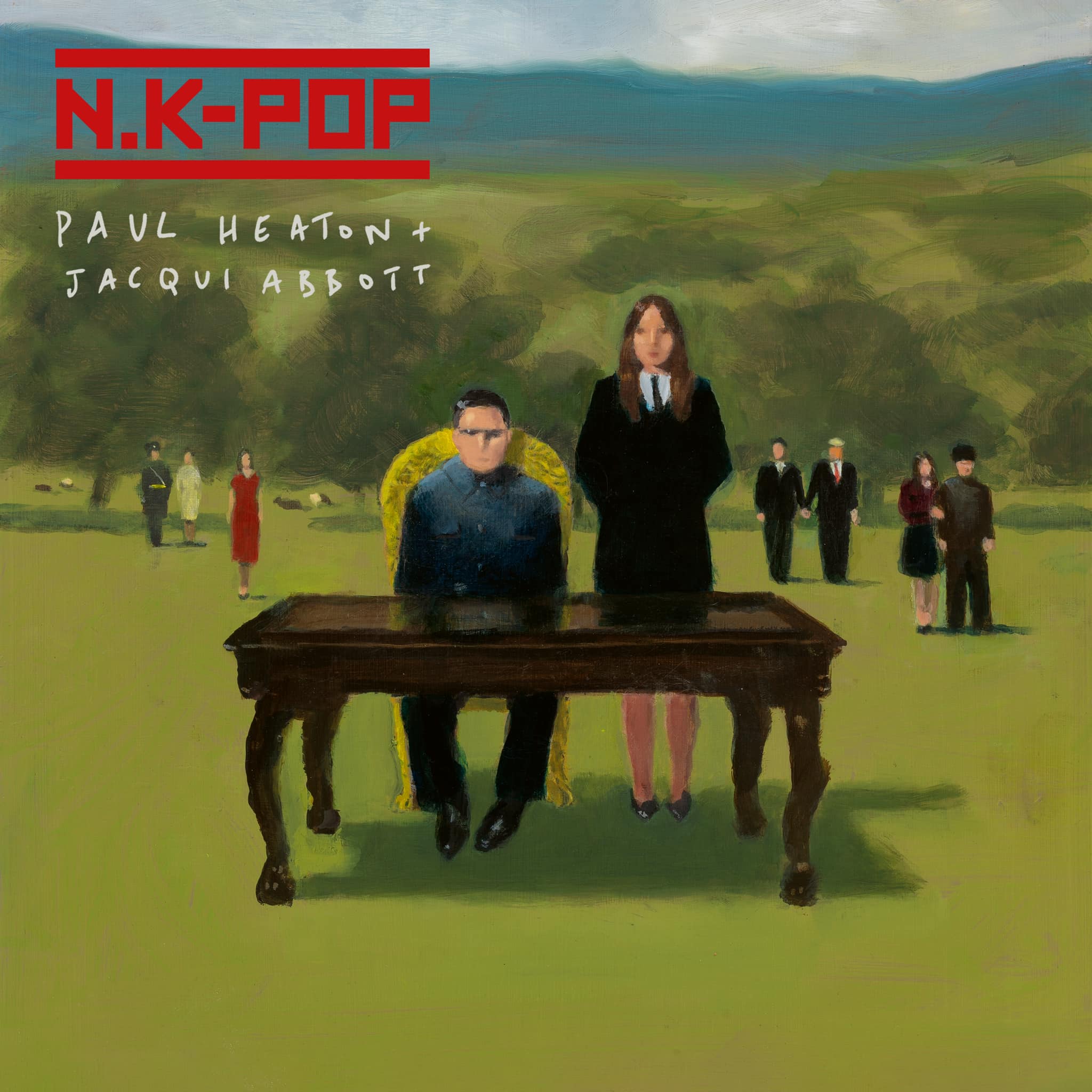

Paul Heaton is on the crest of a wave ahead of the release of N.K-Pop - his fifth album with Jacqui Abbott - via EMI today (October 7).

The British songwriting great was awarded Outstanding Song Collection at the 2022 Ivor Novello Awards for his work with The Housemartins through to The Beautiful South and his current collaboration with Abbott.

The duo hit No.1 with 2020's Manchester Calling (48,560 sales, OCC) and have released three other Top 5 LPs together - 2014's gold-selling What Have We Become (124,280 sales), 2015's Wisdom, Laughter And Lines (80,983) and 2017's Crooked Calypso (61,837).

"I don't usually make records to test people," Heaton told Music Week. "I make them for my crowd to enjoy and love, so I just hope it's received well and people like it. And if it does chart well, that would be great too because the last time we got to No.1 we literally got the train back from London and the pubs shut as we got out at Manchester. It felt like winning the lottery but being told you can't spend it! So if we do get to No.1, or Top 5 or whatever, we can celebrate properly."

On the album title, N.K-Pop, he said: "I imagined this hidden genre. I suppose it's a similar title in a way to [2010 solo record] Acid Country. It's a play on words [ie North Korean Pop] and it's so typical of me - these things used to come through asking, 'Will you approve the release of this song in Korea?' And I always used to mark them back saying, 'Which one?' It annoys me a bit when it says 'K-pop', so it was an obvious thing for me to call it N.K-Pop."

Heaton & Abbott tour UK arenas in November/December, culminating with a headline show at The O2 in London. Tickets are capped at £30.

Paul Heaton turned 60 in May and marked the milestone in inimitable style by putting £1,000 behind the bar of 60 carefully chosen pubs across the UK and Ireland so that fans could have a drink on him. Here, in a Q&A, he discusses his new record, the art of hitmaking and the time he tried to give his catalogue away to the government...

How quickly did N.K-Pop come together?

“It probably took a little bit longer than normal because of lockdowns and Covid in general. I usually like to go away writing to Holland with my wife Linda, but Holland was shut so we went to Portugal for seven or eight days and I did some lyrics. And then Jonny [Lexus, guitarist] and me normally go away to sunny climes to write the songs. This is about two years ago and my mum had just passed away. Jonny and me were writing in this lockdown hotel in Dorking in Surrey and it was all a bit miserable because of what had just happened. Six months later, one of my best friends died in Germany, so I went there and we wrote the next lot just after the funeral there. We went to a place called Bamberg in Germany. I felt sorry for Jonny because normally I'm very buoyant when we're writing songs, but we managed to do it and I'd still describe it as fun. We start with 30 or 40 lyrics, and then get down to about 25 songs. And then as we rehearse, we try and whittle them down to 18 and usually record about 16. So they fall by the wayside as you go on and the album gradually gets smaller and smaller until you're concentrating on perhaps the 12 that are going to get on the album.”

To what extent has your songwriting process altered since the start of your career?

“It hasn’t much. I mean, it's easier now weirdly enough. I hear stories of it getting more difficult, but the only way it gets difficult is if I'm repeating myself tune-wise. I remember writing [1989 hit] You Keep It All In, in my head. It was about probably 1988/89 and I used to record them on tape recorders, but I'd run out of batteries, so I ran up to the garage to get some, but it was 10 or 11 at night and it had just shut. So I'd sing it for five, six, seven hours, all night. I kept on falling asleep and waking up remembering it, thankfully. And then eventually at 8am, I went to the shop for some batteries and wrote it. I'm still like that now but you can write on your phone, so it's a lot easier.”

Do you consciously try to write singles?

“That just becomes apparent. Quite often if I've got a tune in my head, like I did the other morning, that will probably be a single on the next album. And it's pretty obvious when it comes into your head like that, but quite often I'll have a set of lyrics and Johnny will play a set of chords and I'll pick a melody and straight away you think, ‘That could be a single.’ I remember exactly where we were when we wrote most of the songs, all the way back to [The Housemartins’ 1986 classic] Happy Hour. I remember me and Dave [Rotheray, Beautiful South guitarist] writing [1996 single] Rotterdam in Gran Canaria and thinking, ‘Well that's really catchy.’ We used to write a couple and then go down to the bar, and we found ourselves singing it while we were having a drink.”

Have you ever suffered from writer’s block?

“No, absolutely never. I would say that’s because I'm writing... not all the time, but I just wander around and ideas come into my head and I write them down, so I'm fortunate in that way. I would perhaps argue there's been a fallow period where the tunes haven't been brilliant, or perhaps have been weakly produced and haven't blossomed properly, like maybe Acid Country – the tunes were all right, but we never worked properly on trying to get them to sound like singles. Maybe also [2008 LP] The Cross Eyed Rambler. But there hasn’t been a period when it's gone dry, so to speak.”

Your passion for football is well known, have you ever thought about writing a football song?

“It's always been my ambition to have a football song adopted [on the terraces] and Rotterdam was adopted by Liverpool fans originally, I think. So I like that, it’s good fun. I always say to my daughter, ‘Ooh, I'm on telly!’ when the football is on. I refer to football in my songs occasionally, but I wouldn't write a football song. I wouldn't know what to write about really. But maybe if Sheffield United got to Wembley in April…”

Would you consider selling your catalogue?

“Well I tried to give my catalogue to the government. I wrote to Greg Clark, the then Business Secretary [until 2019], and offered my catalogue so that people would gain from hearing my records and it was a way of giving back. But they came back sort of fudged the issue saying, ‘If you want to give some money to charity, why not do that?’ So no, I wouldn't consider selling them. I'd probably give them away just to annoy people. But I didn't make them for money and so the only people I'd like to give them to are the people who've bought them. And I try and do that when I can – when I get money in, I try and give a bit back. I can't imagine there being much of a scrap for the Paul Heaton estate!"

We're sure there would be...

"I'd be concerned that my music would be... I never allow it to be used in adverts or films or anything like that. It's just not what they were meant to be. I sold them once, I'm not selling them again. If somebody's bought my record, I don't expect them to hear it then on an advert for a bank or a deodorant or something like that. That cheapens it, doesn't it? I suppose in the right place I might consider it, but certainly not on adverts to get more money out of people. That's just pathetic.”

What's your relationship with the music industry like these days?

"Great! I mean, I wouldn't say I'm outspoken, but certainly lyrically I've not reined it in much. There are never any editorial questions, they know what I'm like and I'm given an incredible amount of freedom. But then I suppose I've gained a little bit of the freedom through success. People don't really want to hear it - I think they want to paint the music industry as the devil, but everybody's all right from my experience. The Housemartins had been on the dole for two years. I think Hugh [Whitaker, drummer] had been on the dole for four years and we just wanted a wage and that's what we asked for. We didn't want big advances. I'm not making an album to buy a yacht, I'm making an album because I love music. And I've found gradually that more and more people I'm working with within the industry are doing the same.”

You reunited with Jacqui Abbott on 2013’s What Have We Become? Did you expect to still be working together nearly 10 years later?

“I was amazingly surprised, but I had dipped my toe in the water on The 8th, a musical I wrote about the seven deadly sins and [Abbott] sang a little bit on that. And when she sang live, the whole room lit up. Clearly, people had really missed and loved her voice, and that's still the case. They do like me – I do get paranoid that they only like Jacqui! But she's got a voice that connects with people.”

What did it mean to you to be recognised at the Ivors earlier this year?

“Well, it's the first time I've been given any award for songwriting at all. My first words when I got up to accept it were ‘I could have died, it's so late!’ And it's sort of true – I'd just turned 60 – so it meant a lot and it was really nice to experience it with the people I'm close to. In my Beautiful South days I would probably have just taken it in with a pinch of salt and said, ‘Thanks a lot, ta,’ and walked off, so I'm glad they waited because I appreciated it more. Same as having a No.1 whenever it was, 2020? That felt special as well.”

Lastly, your 1989 No.2 single Song For Whoever contains the line: “I love the PRS cheques that you bring.” You must be the only songwriter to have worked ‘PRS’ into the lyrics of a hit song, right?

“Probably, yeah. The song is about making money off women's names and relationships. It was inspired by the Ray Charles album, Dedicated To You. I've got it upstairs and every song on that album is a woman's name, so it just felt doubly cynical.”